Description

×Part 1 in a three-part series examining the surprising effects of the 18th Amendment on the wine industry, primarily in the Napa Valley of California, on American food culture and tastes, and how Prohibition created the conditions for the rise of what many consider to be the greatest wine growing region in the Western Hemisphere. This series is part of an unpublished update to the book Napa Wine: A History. Charles L. Sullivan, called the “greatest living wine historian” (Gerald Asher-Gourmet Magazine) when he wrote the following, died in 2020.

Part I: A certain chemical reaction

The seemingly chance convergence of three historical factors brought national prohibition to the United States in 1920. A long and not particularly successful temperance/prohibition crusade was at work at the turn of the century when the Progressive movement took off, attempting to deal with the nation's problems through corrective public policy. Then, when interest in prohibition seemed to be waning, America entered a war that challenged every citizen to sacrifice for a common cause. Out of the tangle of ardent patriotism, mixed purposes, and cunning deceit came an amendment to the Constitution and a federal enforcement law that gave the country an almost bone-dry public policy. Prohibition was imposed on California and the nation by a well-organized league of zealots who took advantage of the historical moment.

California never succumbed to the lures of the prohibitionists. Offered this policy in election after election, starting in 1914, the Golden State's voters turned down every prohibition proposition on the statewide ballot, even rejecting a state enforcement act in 1920 meant to support the national Volstead Act. When the dust cleared in January 1920, the American people had been saddled with laws that they were willing to try, in a sense of public sacrifice and in hopes of solving a very serious social problem.

THE ATTACK ON SALOONS

Prohibition made little headway in California before 1900. The right of communities to ban liquor, their so-called "local option," was introduced in 1873, but was later thrown out by the courts. Still, restrictions on the sale of liquor were generally accepted as legitimate public policy here. Napa folks understood and accepted this principle in the dry zone set up around the State Asylum there in 1874.

In California the national Prohibition Party, formed in 1869, and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) never had a strong following. But in 1893 the founding of the Anti-Saloon League (ASL) in Ohio brought a strong national dry leader into the field. It was one of the most effective national pressure groups in American history. Its first California chapter was formed in 1898.[1]

Prohibitionist Party Poster, 1888

The ASL's most fertile field here between 1900 and 1920 was in Southern California. There the population explosion since the 1880s had peopled a region that, by 1910, was overwhelmingly white, Protestant, and predominantly Midwest in origin. In contrast, Northern California had been a cosmopolitan demographic mix since the 1850s. In 1910, 68 percent of San Francisco's population was foreign-born and the Bay Area was predominantly Roman Catholic. The new immigration that had flooded the American shores since 1880 had originated mostly in southern and eastern Europe. By far most of these who made it to California settled in the north. In 1910 about 30 percent of Napa County was foreign-born, half of these from Germany and Italy in almost perfect numerical balance. But if one includes the sons and daughters of the foreign-born in the calculus, most Napans were not more than one generation from their Old World origins.

The ASL attack in California was aimed at the saloon and the roadhouse, which most Americans, even most Northern Californians, resented. They had good reason for their concern. Between 1870 and 1915 the U. S. per capita consumption of alcohol had risen almost 50 percent, and most of this rise came in the category of distilled spirits.[2]

After 1900 the country united in attacking political corruption, economic monopoly, and moral disintegration. It was logical that one of the targets of some Progressive leaders would have been the saloon and liquor trade. Progressive muckraker journalists ripped at the corrupt influence of the liquor industry. After 1902 state after state east of the Mississippi passed laws outlawing the saloon. By 1919 every western state allowing women to vote, except California, had accomplished this goal. The Progressive attack aimed at the corrupting plutocracy of the distillers and brewers, who controlled over 70 percent of the nation's saloons before 1917. But this attack remained quite narrow at first. Senator Morris Sheppard, the author of the Eighteenth Amendment, declared, "I am fighting the liquor trade. I am not in any sense aiming to prevent the personal use of alcoholic beverages."[3]

THE CALIFORNIA DRY CAMPAIGN

In California the Progressives tended to be dry in the south and wet in the north. Certain technicalities in California law made it possible after 1902 for counties and unincorporated areas to eliminate saloons and, by 1907, large areas of Southern California had done so. The next year the ASL began an allout campaign to give California a real local option law.

The California wine industry's response to the dry movement's gains was to form the California Grape Protective Association (CGPA), led by Andrea Sbarboro of the Italian Swiss Colony. His goal was to separate the wine industry from the brewers and distillers in the public mind and to promote wine as a wholesome temperance drink. But for now most wine industry leaders were not listening and formed a common cause with the liquor interests in opposing local option. [4]

In August of 1908 Napa's CGPA chapter was formed, led by W. W. Lyman, John Wheeler, Jacob Beringer, and Felix Salmina.

In 1910 the Progressives captured control of the California Republican Party and nominated Hiram Johnson for governor, a supporter of local option but a mild opponent of prohibition. His democratic opponent was Napa's Theodore Bell, whose attitude toward prohibition needs no discussion here. Johnson won and in the historic 1911 legislature one of the many reform bills passed was a measure that became the Wylie Local Option Law. In 1912 this statute brought the dry crusade into almost every local election campaign in the state. Also on the books now were woman's suffrage, initiative and referendum, all supported by Napa voters. Women's votes strengthened the dry forces; initiative and referendum would bring to California ballots a continuous flood of prohibition propositions until 1924.

Hiram W. Johnson, "mild" prohibitionist, staunch isolationist, and champion of the California initiative process.

The first local option elections under the new law took place in April 1912. Sbarboro and Horatio Stoll covered the state carrying the CGPA message. The results were a mixed bag. Most communities voted wet but there were also many in the dry column, particularly from the Central Valley and Southern California. What startled many wine folks were the votes of some communities where the wine industry was of great importance. In Northern California, Los Gatos and Mountain View, both important wine towns, voted dry. In Southern California some local option elections meant that several wineries could produce wine but make no retail sales in their area.

The real test for the North Coast wine region came in the fall elections. Napa County dry petitions placed the retail sale of alcoholic beverages on the ballot in three rural districts. At a time when public opinion polls were not even in their infancy, the outcome of almost any election was in doubt until the votes were counted. St. Helena actually had an ASL chapter that asked voters, "Are not your homes, your boys, your girls and your community of more value than the few gallons of your wine used in the resorts affected by the votes in your district?" In the southern part of the county the battle was heated. Here it was understood that the question was not whether a few swell spas for the rich would lose their liquor licenses, but whether the sordid roadhouses below Napa around Soscol and on the Sonoma Highway would be shut down. Large anti-dry meetings were held here, addressed by Stoll and Gier. The local press was full of correspondence on both sides, the dry forces attacking wine advocates as defenders of roadhouses and saloons.

The end result was a not particularly over-whelming wet vote of 58 percent in Napa County. Only 1,777 people actually voted; a switch of 150 votes would have placed most of rural Napa County in the dry column. It is clear that even in the wine country many were impressed by the evils of the saloon and were willing to get rid of them.

In Sonoma they did just that, at least in the countryside. But the Sonoma ordinance was strictly an anti-saloon proposition and was not meant to touch the wine industry there. When the voting was over Napa remained the only county in the Northern California wine country in which every local option measure had been defeated. By the end of the year California had twenty-two dry towns and seventy-eight dry supervisorial districts.[5]

In 1913 the CGPA was able to get a new Viticultural Commission through the Legislature, proving for the moment, at least, that ASL opposition was not the kiss of death-yet. Not a Napa person was appointed to the new board, which is not surprising, since Napa industry folks had been instrumental in destroying the old board in 1893. In the public discussion of the matter the state WCTU called for the destruction of the California wine industry, "which is responsible for so much that is inimical to the highest welfare of our people." Really what these women were complaining about were the millions of gallons of fortified wines and beverage brandy sold in the country's saloons, which the wine industry was always able to overlook when attacked as part of America's liquor problem. It didn't take California's wine merchants long to get the gist of the ASL program.[6] Their motto said it all. "California Dry in 1914-The Nation Dry in 1916."

In February the CGPA was reorganized with lots more fighting money. Napa's Bismark Bruck was elected vice president. It was decided that he would run for the State Assembly, so that wine advocates would have one of their own on the floor of the legislature. Theodore Bell hit the lecture circuit, taking part in a series of heated public debates with dry leaders. CGPA began publishing a monthly bulletin, "The California Grape Grower," written by Horatio Stoll. This mimeo sheet was the forerunner of his Wines & Vines, which began formal publication in 1919 as the California Grape Grower.

The big fight in 1914 concerned the statewide prohibition initiative that went on the November ballot. It was soundly defeated, with almost 60 percent of California's voters saying NO to "California Dry." In Napa the wet vote was 5,328-2,040, in St. Helena 551-93. Some thought that the wet victory came primarily as a result of the high repute of the wine industry and the effectiveness of the CGPA campaign. Bismark Bruck was easily elected to the Assembly and Theodore Bell became the full time legal council of the CGPA. For him the election had been too close. He was now determined to "take the drunkenness out of drink." He was convinced that the California wine industry had to take a strong hand in trying to reform the liquor industry. If this meant that the saloon had to go, so be it. Otherwise the wine industry would be overwhelmed by the same wave that would destroy beer and spirits. But wine industry leaders in the CGPA refused to back his position.[7]

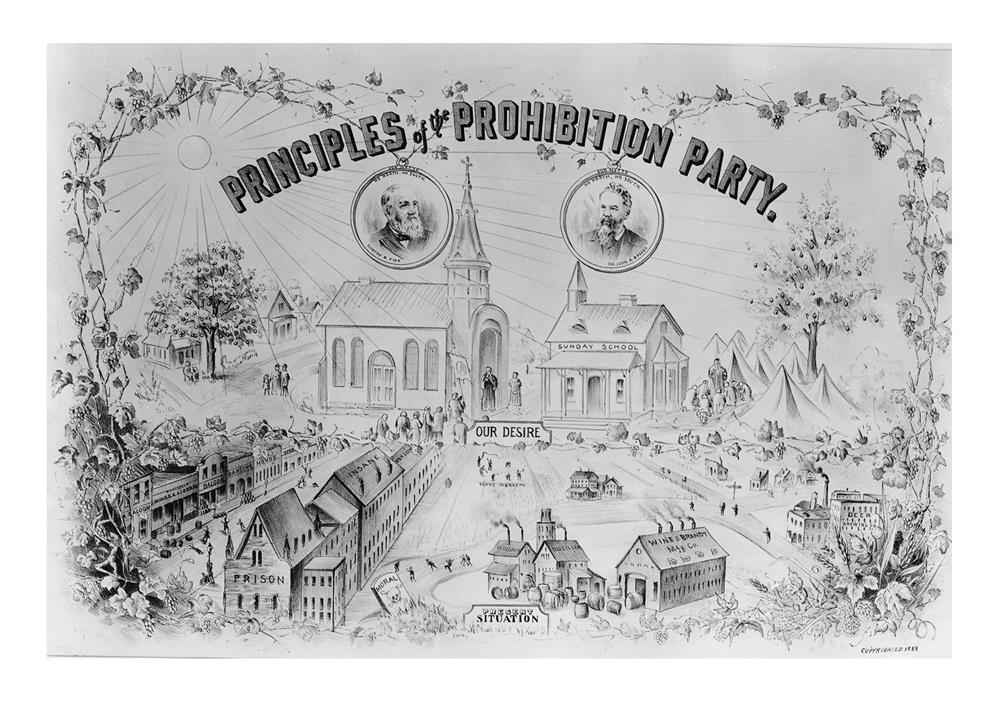

The dry campaign began to intensify after the ASL was able to get two state propositions on the 1916 ballot. One was bone-dry and the other aimed only at the saloon. Theodore Bell saw the handwriting on the wall and again asked the wine industry to disassociate itself from the liquor trade and the saloon in the coming fight. At first the CGPA leaders seemed willing to go along, but in the end were cowed by the economic pressure placed on them by the liquor interests, which controlled a large part of the distribution network for California wine in the east.

California Wine Association advertisement. 1916. (Courtesy of the Unzelman Collection)

Meanwhile the ASL decided to oppose any attempt by the wine industry to take part in the reform, limitation, or elimination of the saloon in California. The league's president made their purpose clear: 'We naturally prefer to fight saloons unsupported by the wine men, and then turn around afterwards and finish off the wine men." Bismark Brock's bill for saloon reform never came to a vote in the legislature, opposed by the liquor interests and the drys.

The CGPA put together an enormously effective campaign against the two 1916 dry ballot propositions. Stoll and his crew produced four one-reel movies which concentrated on the wholesome life of California's small vineyardists. These were distributed free to movie houses. Prizes were awarded to schoolchildren for the best essays on the importance of saving California's vineyards. Along country roads, throughout the state, a billboard would announce the coming demise of the vineyard surrounding the sign. The CGPA stress on this contented and bucolic aspect of winegrowing infuriated the drys, but they could do nothing about it. The CGPA campaign worked. Both propositions went down to defeat, but it was closer than in 1914. Now it appeared that 45 percent of California's voters were willing to sacrifice the state's wine industry, if doing so would destroy the saloon. In Napa the bone-dry initiative lost 5,261-1,985. The anti-saloon measure was a little closer, 4,922-2,329. In November 1916, Woodrow Wilson was returned to the White House for a second term, but ASL leaders were most concerned with the Congressional races. The election upped the number of dry legislators to a point that seemed to promise enough dry votes to pass a prohibition amendment to the Constitution. In California the ASL turned to the national campaign. Their president conceded that "We are much more ready for national prohibition than state prohibition in California." In other words, so far as the ASL was concerned, Californians were going to get prohibition whether they wanted it or not.[8]

Finally California “wine men” got the picture. They now rushed to separate themselves from the image of the saloon and liquor trade. When the CGPA met in San Francisco after the holidays, Bruck, Salmina, and Ewer joined other directors in declaring: "This Association is not wedded to the American saloon." So belated a decision for divorce was doomed to failure. Bruck again introduced his saloon reform bill, which passed the Assembly but failed in the Senate. Meanwhile, John Wheeler didn't need anyone to tell him what a smart Napa vineyardist should be doing that dormant season. He was ripping out vines and planting prune trees. Over 100,000 prune trees were planted in the Valley this season. The number would skyrocket in the next two years, as more than 2,000 acres of Napa vines were uprooted.[9]

The drive toward national prohibition was accelerated when President Wilson called Congress into special session to ask for war against Germany. He got it on April 6, 1917. The fact of war now called for greater efficiency and sacrifice from everyone. Foodstuffs could not be wasted on booze. Our "boys" had to be protected from the evils of drink when they were away from home. Women and girls had to be protected from the evil bred by booze while the "boys" were away. By the end of the summer Congress forbade the use of foodstuffs to produce beverage spirits. For the moment wine and beer were exempted.

In California in the fall the big political question was the Rominger Bill, a proposal that would outlaw the saloon and spirits, but would keep table wine legal. Much of the wine industry, including the CGPA, supported it. But radical drys saw this as a trick to save the wine industry from the ax. Moderate drys were for it. The bill passed the Senate but failed in the Assembly by three votes. Now the CGPA decided to place the bill on the ballot in 1918, but Napa balked. The fact that the ASL was supporting the measure was enough to convince Bismark Bruck that this was the first step on the road to statewide prohibition. Except for Napa, the entire California wine industry got on the Rominger bandwagon next year. Napa's wine continued to oppose these attempts to change the industry's image at this late date. Napa's Frank Busse argued that this proposition "deliberately proposes to protect the rich man's table and to send the poor man to the bootlegger." Cranky as ever, Napa wine men would have none of it and in August voted to quit the CGPA. The Napa leaders' opposition appears to have been ideologically based, really quite idealistic. It certainly did not derive from self-interest. Bismark Bruck's opposition was typical of Napa's independent producers. In June 1918 they canceled the upcoming vintage festival.[10]

In fact, all this sound and fury in California meant almost nothing. The Sheppard prohibition amendment had just sailed through the Senate 65-20. It set forth an almost bone-dry national policy that would outlaw everything about beverage alcohol except legal possession by private individuals for home consumption.

Behind the overwhelming support in Congress was a fear of appearing anything but totally patriotic. A jingoistic anti-German campaign fueled the anti-liquor fires. The drys simply needed to read off the names of the German owners of the great breweries. In Northern California this frenzy was whipped up by such as Stanford's President David Starr Jordan who accused German brewers of having "rendered thousands of our men inefficient and thus crippling the Republic in its war on Prussian militarism." From Britain the words of Prime Minister David Lloyd George were happily spread by the ASL: "Drink is doing us more damage in the war than all the German submarines put together." It would take a Congressman with a very secure seat to stand against the amendment. In December the House voted 282-128 to submit it to the states for ratification. Five of California's nine representatives voted N0.[11]

Vintages: 1914 - 1918

Life went on much as before in the wine country, whatever the threat from dry forces. The Great War in Europe was always on people's minds as it gradually settled into a gigantic stalemate. In the 1914 wine grape season the number of freight cars loaded with lugs of California grapes and headed for eastern markets and home winemakers rose significantly. To date this trickle had not been noticed much by industry leaders, except in Lodi and Fresno, where most shipments originated. The first refrigerated car in this trade had headed for Chicago from Lodi in 1910. By 1915 the number would reach 750 cars.[12]

1915 brought a sudden crash in the state industry that depressed grape and wine prices to levels of the nineties. The downturn was the result of high inventories and overall decline in demand. Actual U.S. wine consumption in 1915 was about 40 percent below the 1910 level. It would rise again during the war, but not to previous levels. The CWA at Greystone honored its contracts but wouldn't buy an additional grape. Much of the white wine crop was not even picked. The general gloom this fall was increased by the death of Jacob Beringer in October. Frederick, the other Beringer brother, had died in 1901.

The Napa vintage in 1916 was a short one. A May 7-8 killer frost destroyed many young vineyards. It was the worst freeze since 1887. Prices rose to more than double the unpleasantly low 1915 levels and the grapes were almost all in when the October rains hit. The resulting wines were of excellent quality with attractive flavor concentration.

Meanwhile the demand for California wine soared and prices went through the ceiling. The war had virtually cut off wine imports from Europe. About 3,000,000 gallons per month were shipped out of the state during the last half of 1917. Napa wineries were virtually empty when the new vintage got under way. Every Napa grape had been sold before one was harvested this year. Weather conditions were good and the tonnage was double the 1916 crop. It was common knowledge that the Valley's winegrowers, to a man and woman, were able to pay off their mortgages this year. Also noteworthy were the 4,000 carloads of California wine grapes shipped east this season, a trade in which Napa was not yet a participant.

In the first months of 1918 all eyes were focused on events in Europe. American troops were pouring into France by the hundreds of thousands. But people still had to tend to business. Vineyards in Napa continued to disappear, 110,000 new prune trees taking their place this season. John Wheeler replaced thirty more acres of grapes, this time with currants. The CWA had given up and was liquidating its huge assets as quickly as possible. Their president stated glumly that "further pursuit of business with a future so uncertain is unwise."

THE EIGHTEENTH AMENDMENT

The course of the war knocked almost everything else off the front page of newspapers in 1918. But the back pages told how dry forces in Congress pushed for full statutory wartime prohibition, to include beer and wine. They finally put it through Congress on November 21, making production of all alcoholic beverages illegal on July 1, 1919. Many wondered at the logic of this measure, since the Armistice had been signed ten days before Congress passed the bill. Dry forces argued that the war was still a technical reality until a peace treaty was signed. A compliant Congress had bought this idea. Logic had nothing to do with the matter. '

State after state ratified the prohibition amendment. The South and Midwest led in the first wave. In California the dry movement worked overtime on the question. ASL spokesman Franklin Hichborn called on his fellow California drys to go over the top, "take the last trench."

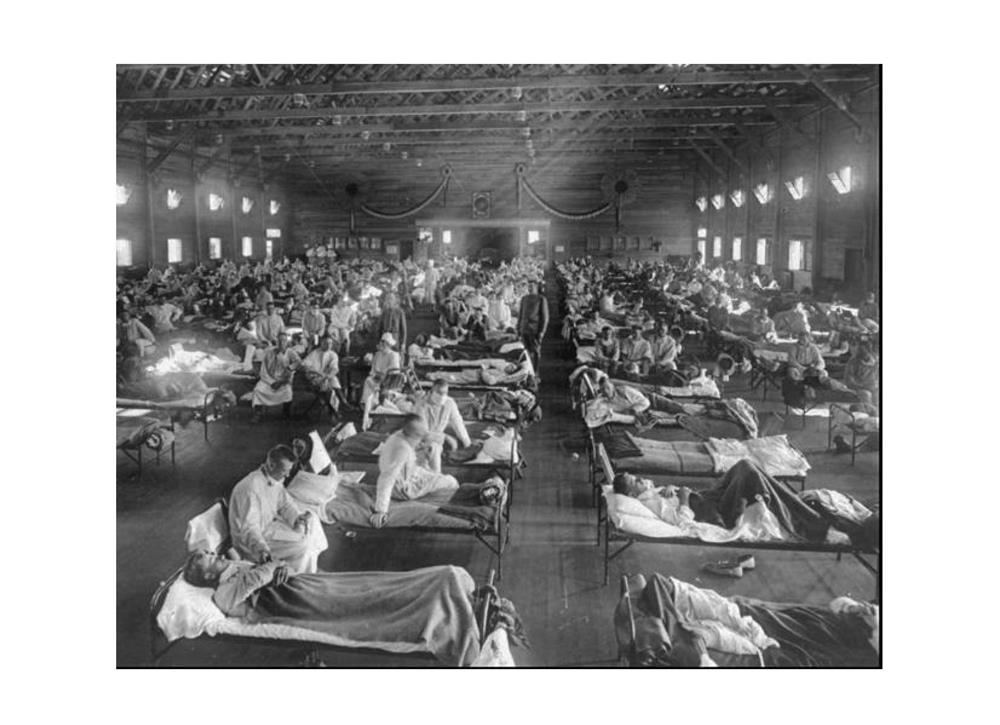

In California the vote on the state prohibition propositions took place four days before the Armistice. At this moment the country was being swept by the worst epidemic of influenza in its history. In Napa the weekly list of sick and dead was appalling. The statewide voter turnout was 35 percent smaller than in the previous off-year election. Both the bone-dry and the anti-saloon measures were defeated.

Overflow H1N1 “Spanish flu” patience in St. Helena.

When the 1918 Napa vintage began in September there was a lot of talk here about the prospects for shipping grapes east-next year. For now it was all pure profit.

Grape quality was ordinary, with a cool fall full of rainstorms. Pickers, mostly in masks to guard against influenza, made wonderful money, working long hours to get the grapes in early. Low sugar was no problem for grapegrowers with these kinds of prices. Throughout the Valley there was a great Armistice celebration after the harvest. But in Rutherford, at the end of the vintage, most of the commercial area of the town burned down.

For all the good times the future looked ominous. Theodore Bell advised Napa growers to prune, cultivate, and hope. He was sure that something would be done to get around the wartime prohibition rule. Meanwhile, the national prohibition amendment still had only fourteen of the necessary thirty-six states on line.

But on January 2, 1919 Michigan ratified. Then between January 7 and 9 five more states came over. In California the Senate ratified on January 10 with a 25-14 vote. The Assembly put it over three days later, 48-28. It took three fourths of the states' approval to get national prohibition, but in individual states a simple majority was sufficient. In historian J. S. Blocker's words, "skillful use of prohibitionist minorities created legislative majorities."[13]

Then came the deluge. Between the 13th and 17th nineteen states ratified the Eighteenth Amendment, and it became law, to go into effect January 16, 1920. To this day no historian has put together the story of how this five-day burst of dry energy was harnessed.

Napa didn't know what to do. The overwhelming rush of dry victories had come in a period of but nine days. No neutral observers had predicted this result. The Star lamented that "the beautiful vineyards that have been the pride of the state are doomed." On February 28 a huge group of growers and producers met at the Liberty Theater in St. Helena. Theodore Bell spoke to the crowd but could offer little but illusory hope. For now the big question was the 1919 vintage; what would happen to the grapes after the July wartime prohibition law went into effect?

CWA tested the waters on July 11 by making a huge shipment of Greystone wine under a bill of lading marked "sacramental and medicinal." No one complained. Meanwhile local eyes were really starting to focus on the eastern wine grape market. A representative of an eastern shipping firm arrived in the Valley in mid-July offering top dollar for red wine grapes. Suddenly there was a huge demand for wooden shook to make lug boxes for shipping.

The crop was in great shape, the largest of the century. Frank Cairns and F. J. Merriam, both local men, led the field here in lining up and organizing grape shipments. Cairns had 200,000 lug boxes ready to go when the Napa grapes started coming in. Their first carload left the Valley on September 12. Within a few days buyers from all over the Bay Area were arriving in the Valley with trucks to haul grapes to Oakland and San Francisco for on-the-spot sale.[14]

People wondered whether the government was actually going to allow home winemakers to produce wine. And what about wineries that did not have special licenses for sacramental wine production? On August 22 Theodore Bell called the office of the Star to say that winemakers should go ahead and make wine. The IRS was apparently holding fire, not knowing the proper course themselves and far more concerned with controlling the flow of hard stuff.

Gradually the wineries started making wine. On September 12 the CWA began accepting grapes from regular suppliers. Then Larkmead and Lombarda started crushing. To Kalon began making "non-beverage wine" on September 26. By the first week of October buyers from the Bay Area were literally cruising the Napa Valley looking for any lots of grapes not yet sold. On October 3 Bell telegraphed the Star to spread the word that home winemaking would be allowed and that the IRS was staying out of the whole wine scene now, so long as the tax revenue laws were obeyed.

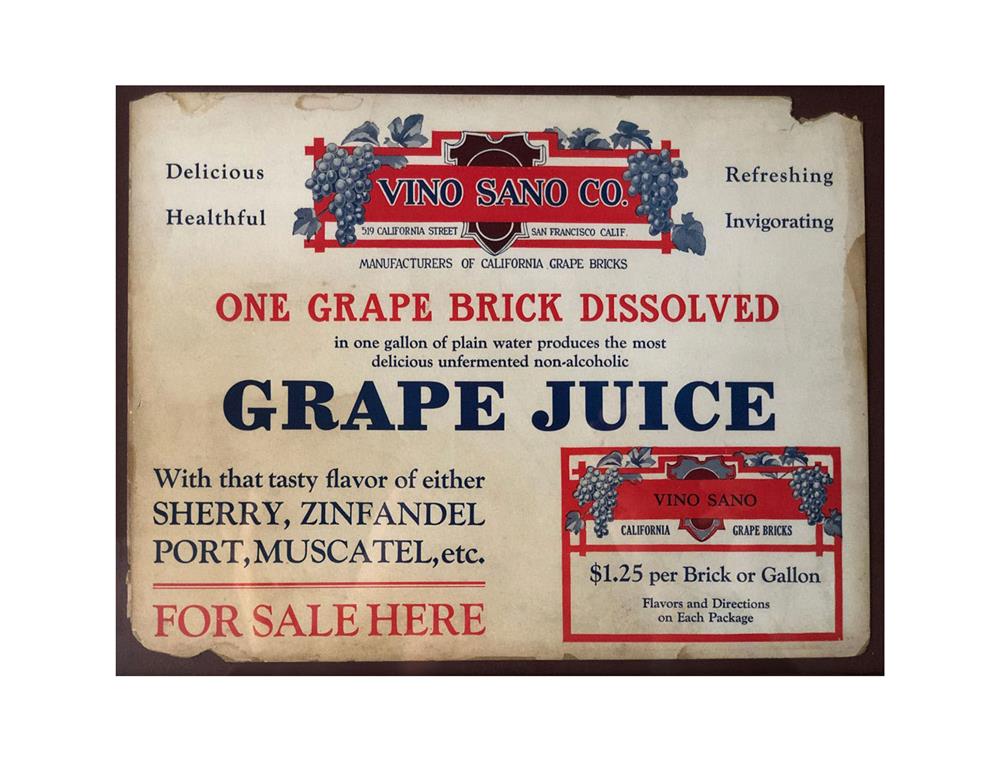

When it was all over at the end of October, Napa winegrowers took a deep breath and surveyed the vintage. Lots of wine had been made. It would work its way into various commercial channels, getting around the prohibition rule, but it all had to be done before January 16. Several, like Louis Kortum and Bismark Bruck, made grape juice to be sold as such. John Wheeler had built a copper vacuum evaporator and condenser to produce grape syrup. If the buyer added four parts water and some yeast, a certain chemical reaction would probably take place. There was lots of talk about alternative uses for wine grapes, but for now the obvious use was eastern rail shipment. This season no less than 9,300 carloads of fresh California wine grapes headed for Chicago, New York, Boston, Newark, and other eastern cities with large ethnic populations that were not about to give up their table wine. And for Napa the San Francisco market also looked very good.

[1] For a good bibliography of American prohibition see: Norman H. Clark. Deliver Us from Evil (New York 1976): 227-235. Joseph P. Kett. "Temperance and Intemperance as Historical Problems," Journal of American History (March 1981): 878-885 is the best discussion of recent prohibition historiography.

[2] Clark Warburton. The Economic Results of Prohibition (New York 1932): 23-72; W. J. Rorabaugh. The Alcoholic Republic (New York 1979): 232-233. High as this figure was in 1915, that for 1830 was 177% higher. In 1990 it was about what it was in 1915.

[3] Clark, 95; James H. Timberlake. Prohibition and the Progressive Movement (Cambridge, Mass. 1966): 156-157.

[4] Sbarboro published several pamphlets on this theme, e.g. Wme as a Remedy for the Evil of Intemperance (1906); The Fight for True Temperance (1908); Temperance vs. Prohibition (1909).

[5] Register, 10/26/1912, 10/27/1912, 11/4/1912, 11/6/1912; Star, 10/25/1912, 11/8/1912.

[6] SBVC. Report for the Years 1913-1916 (Sacramento 1917); PWSR, 1/31/1912, 8/131/1913, 11/30/1913.

[7] Gilman Ostrander. The Prohibition Movement in California (Berkeley 1957):135-138; Arno Dosch. "California Next?" Sunset (March 1916): 22-24; Star, 11/6/1914, 11/20/1914; PWSR, 11/30/1914.

[8] New York Times, 3/27-4/4/1926; Ostrander, 134; Peter Odegard. Pressure Politics (New York 1928).

[9] Star, 3/2/1917, 8/17/1917, 8/31/1917.

[10] NVWLA II: 233; Star, 2/22/1918, 4/19/1918, 6/7/1918; Chronicle, 3/5/1918; PWSR, 3/30/1918.

[11] Clark, 124-125; Odegard, 70.

[12] San Jose Mercury, 9/25/1910; PWSR, 1/31/1915.

[13] Jack S. Blocker. American Temperance Movements (Boston 1989): 106-119.

[14] Star, 2/28/1919, 7/1/1919, 8/22/1918, 8/29/1919, 9/12/1919, 9/26/1919, 10/3/1919, 2/19/1919; Chronicle, 10/11/1919, 10/16/1919.

Author Bio

×"Payemnt Success! Prepping Media..."

"Payment failed! please try again..."